Many of you no doubt noticed the curious game of ping-pong that unfolded in the “Opinions” section of Le Devoir folowing May 19, concerning the identitarian nationalist group Nouvelle Alliance’s attempt to enter the sovereigntist movement and the mobilization of part of this movement to exclude it.

In the first letter, secularist activist Nadia El-Mabrouk complained about the exclusion of far-right elements from the sovereigntist big tent on the pretext that dialogue should always be encouraged. Never mind that, by her own admission, she knows nothing at all about Nouvelle Alliance and its proven links with the far right.

Environmental activist Quentin Lehmann replied the next day, arguing for a clear stance against the far right in pro-independence circles, the obvious corollary of which is zero tolerance for Nouvelle Alliance in these circles.

Playing into the hands of Nouvelle Alliance, on May 27, Le Devoir saw fit to publish a statement from the group (something they also did last December, in response to a column by Jean-François Nadeau). The response was not terribly coherent, as a number of commentators pointed out.

Up to that point, it might have seemed that the exchange was fair game, but on May 28, the daily decided to add another layer by giving the final word to its regular contributor Patrick Moreau, who recently and notably addressed Trumpism and so-called wokeism as two sides of a single coin, and who now offers us a dishonest chronical dripping with bad faith that equates principled anti-fascism with “censorship”.

Montréal Antifasciste wanted to publish a response but, unsurprisingly, Le Devoir did not respond to our request. Below you’ll find our response to Patrick Moreau, who, for someone who regularly uses the word “censorship” to beat up on progressive movements (feminists and anti-racists, in particular), is decidedly unfamiliar with its meaning and definition.

///

The Confusion Between Censorship And Anti-Fascist Resistance Only Benefits The Far Right

Montréal Antifasciste

May 28, 2025

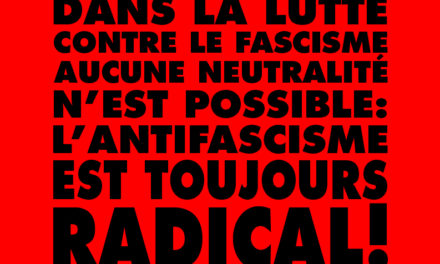

In his response to Quentin Lehmann’s letter, Patrick Moreau creates a curious equivalency between “censorship”—which refers to a limit imposed by an institutional authority, usually the state, on the freedom of expression of a person or group—and a principled decision taken by a subset of civil society to exclude from its ranks actors or ideas whose legitimacy it does not recognize or considers to contravene its principles.

Nowhere in Mr. Lehmann’s text is there any question of “censoring” the far-right group that is at the source of this controversy. Instead, the author invites the public to “s’organiser, se positionner, riposter et ne pas craindre de nommer l’ennemi politique lorsqu’on le discerne” [organize, take a stand, fight back, and not be afraid to clearly identify a political enemy when we see one]. He suggests responding to the far right with “l’éducation, la vigilance et le refus” [education, vigilance, and refusal].

The rejection of a far-right presence in public spaces by the people who use these spaces and not by institutional power is not only legitimate, it is to be encouraged. This is how the far right finds itself, quite literally, marginalized. It is by refusing its presence that we prevent it from becoming normalized and gaining traction.

Since fascism and its variants are anomalies in a democracy, we believe it is justifiable to fight them using extraordinary means. Take, for example, the Battle of Cable Street, when, in October 1936, numerous Londoners mobilized to prevent the British Union of Fascists from marching in the streets of the English metropolis. This confrontation left its mark on history. Was this a case of “censorship”? Countless similar examples punctuate history, including here in Québec, where neo-Nazi groups were literally driven off the streets by popular mobilizations in the 1980s and 1990s.

Montréal’s anti-fascist community has been sounding the alarm for many years about the threat posed by various groups (national-populists, neo-fascists, neo-Nazis, and, in this case, ethno-nationalists) to various sections of Québec society, including people from immigrant communities, the Muslim minority, and LGBTQ+ people. The threat posed by the far right is very real, and history teaches us that it can very quickly move from rhetoric to action. We need only recall January 2017 Québec City mosque massacre.

It should come as no surprise that various sections of civil society, particularly those concerned with inclusion and a mutual life, are taking a stand and mobilizing using their own means to keep the far right out of their spaces, thereby contributing to its isolation and defeat. Whatever some observers may think, this is what democracy in action looks like.

Part of the liberal commentariat, which is always ready to denounce the alleged “wokeist” threat, seems far more willing to defend the far right’s freedom of expression than to denounce its rhetoric. The end result of this charge of censorship in reaction to something that is in no way censorship is a defense of the far right’s prerogative to impose itself in spaces where it is not welcome.

///

Addendum: Failing to publish our response, Le Devoir did publish a much better one on May 31, under the title « La liberté d’expression au service du bien commun », written by Orlando Ceide. The more adventurous will notice the ordinary racism of some of the nationalist old guard, who express themselves freely in the comments section.