Over the last few days, you’ve surely become aware of the controversial bill proposed in Québec. Bill 62 seeks to protect the state’s much vaunted “religious neutrality” and is the latest move in a long standing political debate about secularism and religious accommodations—a debate that particularly impacts Muslim women.

Over the last few days, you’ve surely become aware of the controversial bill proposed in Québec. Bill 62 seeks to protect the state’s much vaunted “religious neutrality” and is the latest move in a long standing political debate about secularism and religious accommodations—a debate that particularly impacts Muslim women.

On October 18, 2017, the nightmare became reality: Bill 62 on religious neutrality was adopted by the National Assembly by 66 to 51 margin.1 This report provides a critical overview of the law and its implications, as well as its historical roots and its place in a larger social context, specifically focussing on the Islamophobic discourse advanced by the mainstream political parties in Québec, as well as placing it within the framework of the increasing normalization of the rhetoric and mobilizing of far-right Islamophobic and anti-immigrant groups across North America since early 2017. We also think it essential that the issue be approached from a feminist viewpoint—as an example among many others of the restrictions and controls women are subjected to by the state, particularly racialized and Muslim women.

Implications of Bill 62

First, the obvious questions: What exactly does this storied law actually mean? How will it affect our lives? Should we be concerned? It’s true that we often exaggerate the impact of new laws and regulations, adopting a sensationalist and catastrophizing tone. Unfortunately, this isn’t one of those times—we really ought to be concerned. Here’s a far from complete list of particularly unsettling constraints introduced by Bill 62:

Bill 62: MAJOR OBLIGATIONS AND RESTRICTIONS2 OBLIGATIONS

(new legal obligations)RESTRICTIONS

(new legal constraints)

- Have your face uncovered if you are receiving or providing a public service;

- All municipalities, transportation corporations, and city boroughs, as well as the National Assembly, must conform with the law.

- Full veils (niqab, burqa), balaclavas, bandanas, and any other clothing that covers the face are banned from public transit and public libraries;

- Ban on receiving or providing services with your face covered in a hospital, unless the face covering is necessary for security or the smooth functioning of the service.

Amended from its initial forme,3 the bill now specifies that requests for “reasonable accommodations” (in exceptional circumstances) can be met if they respect the following conditions :4

- The request must be serious.

- The request must respect the principle of equality between men and women (at least the state’s definition of the concept).

- The request must respect the principle of the state’s religious neutrality.

- Meeting the demand does not impose “excessive constraints” on the rights of others, the functioning of the service in question, or public health and safety.

Note that some opposition parties, including the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) and the Parti Québécois opposed the bill because it did not go far enough.5 Both parties support the complete elimination of reasonable accommodations,6 even when requested for religious reasons. Even without the support of the opposition parties the bill was adopted on the simple basis of the Liberal majority. Any opposition came from parties that found it too lenient but agreed with its basic principles.

It is important to stress that the law is not yet in effect. It has been adopted by the National Assembly, but under the Canadian political system the bill must first receive the final approval of the Lieutenant Governor (representative of the British Monarchy) before finally passing into law. We await the final decision of the Lieutenant Governor imminently.7

Historical Context

Although there’s been a lot of buzz about Bill 62 recently, it’s not really all that new. It was first presented to the National Assembly in June 2015 (more than two years ago) by StéphanieVallée, Procureure Générale du Québec and ministre responsable de la Condition féminine.8 At that point the stated objective of the bill was to “promote the religious neutrality of the [Québec] state.” Vallée offered a more detailed explanation of this objective when introducing the bill:9

“We hope this bill will be greeted by unity, given that it represents a position on which we have consensus. We intend to reaffirm that services offered by the Québec state can in no way be influenced by the religious beliefs of its employees or the people receiving the services. Beyond that, we will rely on clear criteria and the conclusions of the courts to address any request for religious accommodation in the public service.”

Initially, the bill’s raison d’être was to create a framework for addressing requests for “reasonable accommodations” of a religious nature; this would impose a number of restrictions and obligations on Québec’s population, particularly:10

- Employees of public services or institutions would be required to “provide evidence of religious neutrality” at work;

- Everyone would be obliged to have their face uncovered when providing or receiving public services, unless the professional role required covering the face (e.g., a doctor caring for a patient with an infectious disease);

- A “reasonable accommodation” could be considered, but only in very specific circumstances.

Most of these proposals remained intact in the Bill as it was adopted on October 18. The main modifications introduced by Minister Vallée were primarily meant to extend the reach of the law, which now also applies to municipalities and public transit services, as well as the National Assembly, hospitals, and all other public services.11 Alongside religious symbols, the bill also specifically applies to masked militants.12 Really!?! Not only is this a transparent effort to distance the bill from its stated objectives and its anti-Islamic basis, it’s also silly. How do they think that’s going to work? Do they think that militants regularly go to the post office, the clinic, or the SAAQ masked and ready for a demonstration? Obviously not. This is nothing more than a staged use of militants to shift the focus and deflect criticism, to make it look like the law isn’t actually sexist or racist.

It’s essential to understand that Bill 62 is part of a larger political context—the debate on “reasonable accommodations” and religious neutrality that has been raging for ten years in Québec. This “debate”—in reality, a protracted campaign of racist rabble-rousing—can be traced back to late 2006, when a number of very different requests from people of different faiths were all sewn together into a narrative about members of racialized and non-Christian religious communities making unreasonable demands on a generous and long-suffering Québécois majority.13 Various forces worked in tandem to construct this narrative. The Quebecor media empire, of which future PQ leader Pierre-Karl Peladeau was at the time president and CEO, specialized in finding mundane examples of someone asking for some accommodation and turning it into the next day’s front-page newspaper story. With the media setting the stage, Mario Dumont, leader of the Action démocratique du Québec political party, declared Quebec a European society with values based on its religious past, attacked the Liberal government for “being on its knees” before immigrant communities, and called for measures to reinforce Quebec’s “national identity” and protect its “traditional values.”

Next, the city council of the small town of Herouxville made a decisive intervention, passing a racist “code of conduct for immigrants” that played on stereotypes of ethnic and religious minorities, particularly Muslims, implying that they needed to be told not to engage in misogynistic practices such as stoning women and genital mutilation. Among other things, the Herouxville code explained, “The only time you may mask or cover your face is during Halloween, this is a religious traditional custom at the end of October celebrating all Saints Day,” and that “the lifestyle that [immigrants] left behind in their birth country cannot be brought here with them and they would have to adapt to their new social identity.”

Herouxville made headlines around the world. Fearmongers had succeeded in whipping up a generalized atmosphere of racist xenophobia, framed also as a criticism of the provincial Liberal government, accused of being “soft” on immigrants, which would reverberate for years to come. (It might be noted that the man behind the Herouxville resolution, André Drouin, was later active in the Canadian far-right group RISE Canada, led by Ron Banerjee, and for a while associated with the openly fascist Fédération des Québécois de Souche, which, following his death earlier this year, eulogized him as a “courageuxcombattant” in the pages of its magazine Le Harfang.)14

The Liberals under Jean Charest tried to deflate this upsurge by setting up a roaming commission led by intellectuals Gérard Bouchard and Charles Taylor, to hear people’s concerns and table recommendations on how to deal with the “crisis” of requests for reasonable accommodations. The Bouchard-Taylor Commission became a platform for racists across Québec to come out and complain about Muslims and Jews and Sikhs (but especially Muslims), while at the same time legitimizing the initial fiction that growing immigrant populations represented some kind of crisis that needed responding to.

In late summer of 2007, the Parti Québécois proposed a “Quebec Identity Act” which would have removed the right to vote in certain elections from people who failed to pass a French exam and / or would not pledge allegiance to the Québec nation. Then former Liberal MLA Christine Pelchat, as head of the Quebec Council on the Status of Women (a government body), asked the provincial government to pass regulations forbidding public sector employees from wearing “religious clothing,” a call that was echoed by leaders of the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec (FTQ) and the Syndicat de la fonctionpublique du Québec (SFPQ), two of Quebec’s largest trade unions, in their statements to the Bouchard-Taylor Commission in December of that year.

Indeed, sadly, much of the institutional left at the time found itself unable or unwilling to intervene against the rise of racism, as significant sections of not only the trade union movement but also Québec Solidaire, and many whom we would normally assume to be “on the left,” were invested in a white fantasy about a progressive Québécois nation besieged by hostile and right-wing alien forces, and as such either remained silent or actually voiced support for restrictions on minority rights. It was largely outside of the institutional left, in a loose coalition of groups around the organization No One Is Illegal, the Reject Intolerance in Quebec network, that opposition to this racist wave manifested itself.15 While no new legislation came out of all this, the 2006–2007 “reasonable accommodation” drama served to establish a certain narrative and framework, in which Islamophobia, and most especially a fascination with Muslim women’s clothing choices, became central reference points. Although the media attention abated somewhat, racist myths and fears about Muslims continued to advance just under the surface, throughout Quebec society—most especially, it should be noted, in those areas with the smallest numbers of Muslims.

Fast forward six years, to 2013, a few months after the Liberals lost power following the largest student strike in Quebec history. 2012 had been a massive advance for the radical left, and a potential setback for the neoliberal agenda in Quebec, as hundreds of thousands of people had taken to the streets, tens of thousands repeatedly facing off against police, defying the law, risking arrest, all in the context of a strike against university fee increases, framed by the student leadership in terms of class and anti-capitalism.

Following the Liberals’ defeat due to the strike in 2012, the Parti Québécois, under Pauline Marois, took power. Wasting no time, the themes and narratives from 2006–2007 were dusted off and put to new use, as a so-called “Charter of Québec Values10” was proposed, which would bar public sector employees from wearing “ostentation religious symbols” at work. Turbans, yamulkes, and most especially hijabs, burqas, and niqabs were to be forbidden.

The “Charter debate” in 2013–2014 renewed all the racist energies of 2006–2007. Pro- Charter forces held demonstrations of tens of thousands of people mixing secularist, feminist, anti-Muslim, and anti-immigrant themes. While Québec Solidaire objected to it in the form proposed, it insisted that it too was in favour of a modified Charter. Important sections of the Québec feminist movement—historically, the strongest feminist movement in Canada—rallied in favour of the Charter, as conspiracy theories were spread accusing the Québec Women’s Federation (which was anti-Charter) of being funded by Saudi Arabia or Iran to advance the “Islamist” agenda. (Meanwhile, less than two years after the 2012 strike, not much attention was paid as the PQ enacted its own series of austerity measures.)16

While the Charter was not passed, as the PQ lost power to the Liberals in April 2014, something had been set in motion and would not be easily stopped. The years following saw a steady increase in Islamophobic organizing online and the establishment of actual organizations like PEGIDA, les Insoumis, La Meute, and the Soldiers of Odin, many of which had opposition to “radical Islam” as their sole raison d’être. The growth “from below” of such organizations and the nature of their racist fixations were an inevitable result of the racist fearmongering and manoeuvring “from above” that significant sections of the media and political establishment had been engaging in for years.

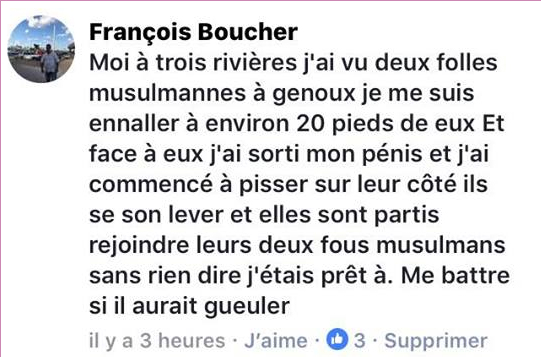

The impact went beyond the growth of far-right organizations. Each of the mobilizations around racist legislation mentioned above was accompanied by widespread harassment of Muslim women wearing head coverings, ranging from being insulted, yelled at, threatened, spat at, slapped, having their head coverings forcibly removed, etc. Horrifically, following the passing of Bill 62, one white man from Trois Rivières felt empowered to post online about how he had exposed himself and urinated at two Muslim women and was prepared to beat them or anyone who would intervene,17 as activist groups began receiving reports of women being harassed while taking public transportation. An informal online survey of Muslim women in the province in December 2014 had found that of 338 respondents, 300 had suffered verbal abuse during the period of the “Charter debate.” Muslim women daycare workers in Montreal’s St-Henri neighbourhood had also received death threats and threats of rape after a photograph of them wearing niqabs went viral on Facebook. Halal butcher shops were vandalized, as were mosques. The day after the PQ was defeated in 2014, an axe was thrown through a window at the Centre communautaire islamique Assahaba in Montreal with the words “Fuck Liberals” and “we will exterminate Muslims” written on it; later that same day, someone rode up on their bicycle, took out a baseball bat, and smashed the windows of three cars in front of another Montréal mosque while their owners were inside saying their evening prayers. Violence against Muslims culminated this year in the massacre at the Islamic Cultural Center in Ste-Foy on January 29, where six men were killed and nineteen wounded; an attack that also, obscenely, served as a signal to Islamophobic far-right groups like La Meute to start taking to the streets in unprecedented numbers.

While Bill 62 may be struck down by the courts, just as the Quebec Charter of Values was bound to be had it passed, the real point of these manoeuvres is to send a message about who belongs and who doesn’t, whose culture is legitimate and whose is “foreign.” In a situation where many Québécois feel under pressure from neoliberalism and also feel threatened by demographic changes here, these laws are an attempt to establish who will be in charge, who will be maitre and who will be maitrisée, who will be allowed to feel they are chez nous and who won’t. The true goal is not a whites-only society, or a society where everyone has the same religion, but rather a society in which everyone who is not a white Québécois is made to feel insecure, at risk, a potential target—and as a result, the racists and misogynists hope, will be subservient and won’t step out of line.

Opposition to Bill 62: A Fundamentally Feminist, Anti-Racist, and Anti-Fascist Issue

It’s clear that the text of Bill 62 objectively reflects the previous failed Québec Charter in what it imposes—the difference being that Bill 62 has been adopted and has far greater reach. This is a problematic and troubling law for a variety of reasons. To begin with, it does not itself respect the equality of men and women! As it primarily targets veiled Muslim women, it imposes restrictions, obligations, and controls that disproportionately affect women. More generally, it is one example among many of a government—one made up largely of white men to boot—that is imposing on women rules and regulations about how they choose to dress, for the most part racialized women. Of course, while they are insistent that the law “applies to everyone,” the fact is that it is a law meant to legally enforce the state’s “religious neutrality.” As such, it’s clear that the main target will be those who cover their faces for religious reasons. Regardless of the specifics of the text or the law’s “greater reach,” in practice, it explicitly targets and sanctions veiled Muslim women.

Which brings us to our next point. Does not the liberal concept of “neutrality of the state” presuppose that that our beliefs will not be imposed on others? Without getting into all of the philosophical and ethical principles, is it not clear that this law violates the essential logic of its own core principle? We can only conclude that the government ceases to adhere to its own principle of “neutrality” when it takes measures to impose the beliefs and values of a standardized Québécois society on Muslim and / or racialized women. It’s hypocritical, transparently so.

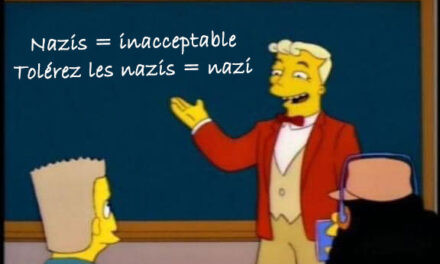

From an anti-fascist point of view, this law is very dangerous, especially in the current political climate, most particularly since the election of Donald Trump to the American presidency and the killings at the Ste-Foy mosque in January 2017. In effect, since the beginning of 2017, there has been a noticeable and worrisome increase in mobilizing on the part of a number of far-right groups in Québec—notably La Meute, Storm Alliance, and the Soldiers of Odin. Islamophobic, racist, and anti-immigrant groups obviously feel encouraged and validated by the adoption of Bill 62, which normalizes the rhetoric and discourse we are hearing from groups of this sort in Québec and elsewhere. In Québec, this normalisation, and the growth of the far right in general, takes a particular form—specifically, an anti-Islamic form—rendering an Islamophobic, racist, and sexist discourse ubiquitous not only among far-right groups but also, and perhaps more disturbingly, in our political institutions and our mass media. We can see clearly the concrete outcome of the spread of this discourse and the normalization of this increasingly extreme rhetoric when we consider the recent increase in hate crimes committed against Muslims, when we reflect on the spectacular murderous violence committed at the Ste-Foy mosque in January, and when we fail to call Alexandre Bissonnette a terrorist, knowing full well that were he a Muslim we wouldn’t hesitate to do so.

This law poses dangers that go far beyond what it itself imposes; it represents an acceptance and systemic buttressing of hateful ideas and an increasingly grave Islamophobia. As feminists, anti-racists, and anti-fascists, we must take a firm position against this law and denounce it at any cost. We must also show—not only verbally but in action—our solidarity with Muslim women for whom this law may soon be a daily reality.

References

[i] http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/510664/adoption-du-projet-de-loi-62 ; http://www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/travaux-parlementaires/projets-loi/projet-loi-62-41-1.html

[ii] Idem. ; http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/politique/politique-quebecoise/201710/18/01-5140396-le-projet-de-loi-62-adopte-fini-le-voile-integral-dans-les-autobus.php

[iii] http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/510664/adoption-du-projet-de-loi-62

[iv] Idem.

[v] Idem. ; http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/510664/adoption-du-projet-de-loi-62

[vi] http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/politique/politique-quebecoise/201710/18/01-5140396-le-projet-de-loi-62-adopte-fini-le-voile-integral-dans-les-autobus.php ; https://coalitionavenirquebec.org/fr/presse/neutralite-religieuse-la-caq-abrogera-la-loi-62-et-fera-adopter-une-veritable-charte-de-la-laicite/

[vii] http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/politique/politique-quebecoise/201710/18/01-5140396-le-projet-de-loi-62-adopte-fini-le-voile-integral-dans-les-autobus.php

[viii] http://www.fil-information.gouv.qc.ca/Pages/Article.aspx?idArticle=2306104597

[ix] Idem.

[x] Idem.

[xi] http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/510664/adoption-du-projet-de-loi-62 ; http://www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/travaux-parlementaires/projets-loi/projet-loi-62-41-1.html

[xii] http://www.tvanouvelles.ca/2017/10/18/le-projet-de-loi-sur-la-neutralite-religieuse-adopte

[xiv] Le Harfang Vol. 5, #5, juin/juillet 2017. It is worth quoting the FQS’ Rémi Tremblay, accurately describing the impact Drouin had had: « Le génie du Code de vie d’Hérouxville ne fut pas d’interdire certaines pratiques liées à l’islam, comme la lapidation, mais bien de faire réaliser à l’ensemble de la province le genre de pratiques qui pourraient fort bien arriver avec ces nouveaux venus provenant de pays où ces pratiques barbares sont us et coutumes. Le but de Drouin ne fut pas l’interdiction dans ce petit village perdu de ces actes barbares, mais bien de réveiller le Québec. Ses détracteurs les moins hostiles parlèrent d’un geste maladroit alors qu’au contraire, ce fut du génie politique. Un petit conseiller municipal sans pouvoir ou influence parvint à faire des pratiques musulmanes le sujet de l’actualité durant des mois. Il ne s’agit pas de maladresse, mais de grand art! »

[xv] http://www.dominionpaper.ca/articles/1589 ; http://solidarityacrossborders.blogspot.ca/2007/02/no-one-is-illegal-montreal-statement-on.html

[xvi] See Partisan #49, « Austérité, racisme, islamophobie : bâtissons notre opposition de classe ! ». http://www.pcr-rcp.ca/fr/3589 « Hausses régressives de divers tarifs (frais de scolarité universitaires, services de garde, électricité) jumelées au maintien des importantes baisses d’impôt consenties aux entreprises par les gouvernements précédents ; coupes systématiques à l’aide sociale, dans la santé et le système d’éducation ; promotion d’un modèle de développement tous bénéfices pour les grandes sociétés minières et pétrolières, au détriment des droits territoriaux des nations autochtones et de l’environnement : la liste est longue et il n’est pas besoin d’en ajouter plus. »