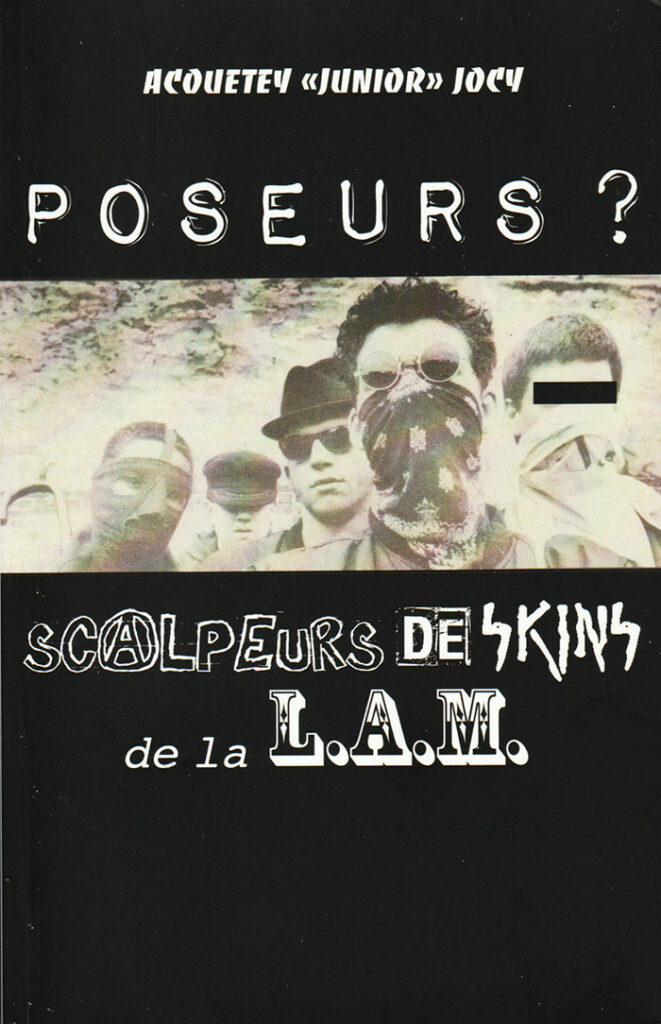

In September 2020 (yes, it was more than a year ago. . .), we met with Baron Noir, cofounder of the Ligue Antifasciste de Montréal and author of the book « Poseurs? Scalpeurs de skins de la L.A.M., which we highly encourage you to acquire and read.

In September 2020 (yes, it was more than a year ago. . .), we met with Baron Noir, cofounder of the Ligue Antifasciste de Montréal and author of the book « Poseurs? Scalpeurs de skins de la L.A.M., which we highly encourage you to acquire and read.

We wanted to dig a little deeper into to some of the issues that we thought were important and that show certain similarities between the situation in the 1990s and what we face today.

///

One theme that was particularly important to us and that we paid close attention to is the ties between the counterculture and both fascist and antifascist groups. How exactly did that work in LAM’s day?

I could take the example of the Rockabilly groups that are very present in the book. How did they end up there, given that they aren’t particularly anti-fascist by nature? As I make clear in the book, in Montréal, at that point, there were Rockabilly people who used the Confederate flag with all the stars and others who used the five-star “rebel” version. In Montréal, their leader was Haitian, and the whole gang was multiethnic. They took a gang-controlled territory approach, and together took the steps necessary to protect their territory, which was [the club] the Dôme, and its surroundings. Obviously, they ended up in conflicts with the Nazi skins who wanted to come to the club, which was somewhat of an underground club, more or less goth, or new wave. At its base, this Rockabilly scene was not anti-fascist, as such, but it became so in the conflict with the Nazis.

Similarly, we could take the example of certain bikers who helped us out. These bikers weren’t anti-fascists. We had a connection to Gros Michel, who worked at Foufs,[1] [The Nazis] were stupid enough to attack his house, so he launched a “Doc Martens boots taxing contest”. That was quite a mess, because some guys who had nothing to do with anything got beaten up (laughs). . . . It went a bit too far, obviously. We found ourselves with the bikers because, as they saw it, although there might have been some of them who agreed with the neo-Nazis, they didn’t want to make any noise about it, but some stupid little twits had to stir shit up and piss everyone off. I’m not talking about Gros Michel, who was genuinely anti-fascist, but about certain bikers. That’s how they came to be part of this story.

The way you tell it creates the impression that it just takes one person for a group to politicize or throw their weight behind one side. . .

One key person is enough. Take a guy like Gros Michel, I never knew if he was a member of the Hells [Angels] or whatever, but he was very respected in that milieu. He had a finger in that pie, and he was sort of our protector; he helped us enormously, because people were afraid of him. In reality, he didn’t do much, but just the fact that people knew he was on our side set the tone. For example, at Foufs, we could just as well have been seen as little shit disturbers, but they decided to ban the neo-Nazi skins. That meant that because of the stupidity of the Nazis who came to harass people, that entire milieu, the Foufs scene, everyone, was against that shit. That was enough to rally the underground groups against them, because they pissed everyone off, an entirely stupid strategy. Even the skaters opposed them.

At the other end of the political spectrum, at that point, the neo-Nazis were present in the metal scene, via NSBM, one of the most important recruiting grounds for a group like Atalante.

That’s true. The Nazis worked around the underground metal groups. There was the Viking and Celtic tendency that was an omnipresent backdrop for those groups, which developed barbarian and pagan aspects, themes that were also taken up by the far right.

What scared me, something we paid attention to at the time, was a tendency for the kids to gravitate to the most attractive group, toward the group that seemed the most powerful, the one with the most intimidating look, for example.

At that age, you need models, and it is possible to offer a positive model. We, as you can understand, didn’t want to leave the traditional skin model to the Nazis. The fact is that the media did a lot of damage by associating the skinheads with neo-Nazis. We wanted to show that there was an alternative, and there were music groups that played a very important role in that, Me, Mom and Morgentaler, for example, a legendary local group. Then there was Banlieue Rouge for the punk aspect. And there was the ska element. These two groups would prove to be extremely successful as things unfolded. As far as the look goes, music is very important to young people. So, on the one hand, it’s necessary to offer a positive model and, on the other, there’s educational work that needs to be done.

Rappers, however, didn’t know anything about the skin movement and told us “we smack anyone with a shaved head who’s wearing docs.”

We were able to recruit in the milieus of all the groups that advocated for unity and revolt.

Initially, LAM developed as an anti-fascist street gang, before becoming a structured, financed, legal group. Can you tell us more about that process?

LAM started out as a gang, but gangs like that don’t really exist anymore, gangs not based on drugs and money—cultural and political gangs. We didn’t associate with the street gangs

You talk about anti-fascism. What is anti-fascism? When you say that you’re a coalition of grassroots groups, I’m pleased to hear that. What are we struggling against? Is it just against small fascist groups? Or do we want a better world? What I find most appealing at the level of action is groups like Greenpeace that carry out actions all over the world that have a lot of impact, but always financed by their members, which is awesome. Us, where we took a hit, if you read the book, was being financed by the unions and professors close to the Parti Québécois, and then politics entered the picture, although I really wasn’t there anymore by then.[2].

A question about repression: in the book you talk a little bit about the repression you experienced, but, at the end of the day, it doesn’t seem that there was that much police repression.

That’s right. The cops were very present on the street. They had fewer cameras, but they patrolled a lot. Among ourselves, we had certain rules; for example, when we went out in force, there were no knives. We took truncheons and batons but no knives, because if someone got stabbed. . . I know how that can fuck up your life, a youthful error you are going to regret.

We were always careful about that, but we didn’t avoid carrying out actions. What was very useful was that the punk scene was extremely active, which provided a lot of protection: the concerts, the small shows, the minor bands. Some people had their moment of glory. It was a bit of a cat and mouse game with the cops once things started to heat up.

It became possible to get subsidized by the teachers’ union, but they said “this won’t work if you’re violent,” so we decided to officially abolish our security service but, at the same time, to create Cyber Punk, a parallel gang. To avoid creating a link, we said we weren’t really part of LAM, when, in fact, we were. Cyber Punk eventually died, and we had the first wave of SHARP, in the early 1990s. It also came out of LAM, but it was made up of thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds, so they were too young to be members. In 1991–1992, there was a small SHARP group that was very violent. That allowed us to keep a foot on the street, as far as anti-fascism goes, but it didn’t look good, because they beat on just about anyone. . .

It’s also a lot of work to take the step from a group of friends that come and go to a political group with a constant presence—to develop a militant group.

Are you against something or for something? We kept an eye on the right-wing groups, but basically we were a progressive organization with a branch, a sort of anti-fascist security service, that carried out actions.

I’m more in favour of prevention than repression, and that has to come from the anti-fascist groups themselves. But that has to be changed within the groups themselves. Us, when we started out, when we were a big gang, there were a lot of people who wanted to come along for the show, for the power, and that’s why we didn’t give the LAM patch to just anyone.

Sometimes people who weren’t members acted in our name, which we simultaneously liked and didn’t like. It’s like Machiavelli says in the The Prince, there needs to be a balance between fear and love. People need to love you and fear you at the same time. I recognize that we lost the capital of “love.” We had the capital of “fear,” but you have to win people’s hearts.

In your case, we note that the fascists blamed you for a lot of things you never did.

Among secondary school students, we had a lot of influence with those who were fed up of being fucked with by puerile little skins—we were a bit like Robin Hood figures. The media also helped us out. There are good journalists who are able to provide a positive image of what you’re doing. Even if the major media loathes you, make use of any platform they leave you. You have to be loved but feared. We also had the opportunity to get television coverage, which provided incredible visibility. So why not, if people speak well of you.

Regarding violence, my position is self-defence. Yes, we engaged in major shows of force, because, as you said, sometimes fireworks are necessary. We wanted to make a very noticeable show of force: there were fifty of us, and we made tour of the town, a real Western (laughs). Besides that, it was more: “We won’t hunt you down, but you have to stay out of these territories. Don’t piss us off.” We took self-defence courses, everyone had their own background, and we trained. We didn’t do this in the spirit of our French skin hunter friends: if you see one of those guys, you fuck him up. It’s not the same story here. It’s some little kid who has become a skin. You scare him, but putting him in the hospital could be counterproductive. Even an old knucklehead, if you smack him around, will that change his way of thinking? He’s a product of society, so the whole system has to be changed. There’s systemic racism, which means that there are people who agree with the dominant ideology, with white supremacy, and they’re struggling for something they already have! If they think it through, they already have white supremacy. It’s subtle, it’s camouflaged, but it’s clear that we live in a Eurocentric epoch. European culture, the West, is dominant now. That was the case forty years ago, and it’s still the case. That’s what needs to change, the mentality of this old Western culture that dominates everything.

The little groups of Nazi sympathizers, a few years from now, they’ll e gone. But look at the Front Nationale and the Rassemblement Nationale in France; nowadays, it looks like they are the main party in France. Did they succeed or did they fail? They have managed to mainstream themselves.

When it comes to the struggle against the more radical groupuscules, we are seeing good results, but it is very difficult to influence the public at large.

In the end, you have to try, otherwise it will never happen. I see that as being part of a larger battle against the existing economic system. My criticism of the left-wing parties, apart from the most extreme examples, which have no influence, is that they forget the fundamentals of anti-capitalism. As I say in the book, originally the anarchists and communists were on the same page; the communists didn’t want the state—they wanted to take power, but, ultimately, they wanted to get rid of the state.

What are we fighting against? What is capitalism? Returning to the fundamentals: you vote for a party that is there to maintain capitalism, even though you have no capital. They’ve succeeded in dividing the working class. They know full well that their interests are not our interests. Do you have capital, property, financial assets, industrial assets? Do you own a factory? Are you a property owner? No, but you vote for them and keep them in power. We’re all in the same shit, because even the left-wing parties want to maintain all of that. So what are we struggling against? Against something absolutely enormous.

In Québec, we have corporate unions. You have a carpenter’s card, a masonry card, or some other card. Who gives a shit about anyone else? It’s everyone for themselves. We’ve got to rebuild class unity, get involved in the unions, in union struggles. The working class hasn’t disappeared. The working masses are still there. We could also form coops.

I see anti-fascists as the working class’s security service. I come back to the idea that it’s necessary to offer a positive model, because there are fragile young people that need guidance who must be won over. In the end, when you think about it, anti-fascism encompasses the vast majority of people—even the people who live quietly, the mainstream, who don’t want violence, even people with conservative views. If you talk to them about violence, about neo-Nazis, you will see that there is a limit, a line that can’t be crossed.

So it is necessary to do positive things, and not just be anti, anti, anti. You have to be pro. At the same time, you can’t fall into “peace and love.”

Suggestion from Baron Noir:

- Watch the film The Corporation, by Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott

- Read the book Fascism and Dictatorship, by Nicos Poulantzas

[1] The bar Foufounes Électriques.

[2] Note from Montréal Antifasciste: The process by which LAM was coopted is not the object of this interview (Baron Noir did not participate in the “street gang” phase of LAM’s history and had nothing to do with the evolution of the collective after he left for France in the summer of 1990). We recommend the following texts to interested readers: “Cops and LAM Go Hand in Hand,” “Après les émeutes de Québec, défendons le droit d’expression” (in Commission #1, https://montreal-antifasciste.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/commission1.pdf), and “La LAM Une Entreprise Hasardeuse?” (in Commission #2, https://montreal-antifasciste.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/commission2-1.pdf). Nonetheless, the author touches upon the dubious orientation the collective after his departure in the final chapter of his book.

The truth is that the degeneration of LAM went far beyond accepting subsides from unions. As we mentioned in our article “MAXIME FISET AND HIS CENTER DO NOT SPEAK FOR US!” (https://montreal-antifasciste.info/en/2017/11/27/maxime-fiset-and-his-centre-do-not-speak-for-us/): “Closer to home, the so-called Ligue antifasciste mondiale (LAM) was active in Montreal during the nineties. The product of street fighting with neo-Nazi boneheads but under growing police pressure, LAM turned primarily to gathering information and specializing in statements to the media. One of LAM’s key priorities was to criticize other antifascist organizations, particularly the Centre canadien sur le racisme et les préjugés. In 1993, when the largest antifascist demonstrations in Montreal in many years were organized against the presence of representatives of Toronto’s neo-Nazi Heritage Front and France’s Front National, LAM acted primarily to sabotage the militant mobilizations. They even went as far as denouncing the anarchists behind the magazine Démanarchie to the police, and then publicly in the media following the Saint-Jean riots in Quebec City, in 1996. Shorty thereafter, it was learned that LAM had been sharing information on the left with the police for years.”