An anti-immigration rally organized by Groupe Sécurité Patriote (GSP) near the border crossing in St-Bernard-de-Lacolle, on October 19, 2019.

In 2019, the far right in Québec was a lot quieter than it had been in 2018 and 2017, the year that Montréal Antifasciste was formed. There are a number of reasons for this:

- the CAQ taking power in October 2018 demobilized a certain number of members in the organized groups, who found themselves with a government that was at least partially sympathetic to their identitarian demands (of course, this is not to in any way suggest that these far-right ideas and currents have magically disappeared);

- major internal conflicts that had been building for some time finally exploded in the past year, particularly within La Meute but also within various groupuscules, including the Gardiens du Québec (LGDQ) and Groupe Sécurité Patriote (GSP), destabilizing the most important and best structured groups;

- taking advantage of the weakening of the key groups, a certain number of marginal figures and “problematic leaders” (for example, Pierre Dion of the Quebec “Gilets jaunes” [Yellow Vests], Luc Desjardins and Michel Meunier of LGDQ, as well as other distasteful individuals like Diane Blain) have played a more important role, further discrediting and demobilizing the national-populist far right;

- the sustained work of antifascists in identifying and denouncing the more radical elements, meaning, the full-on fascists and neo-Nazis in Québec’s far right, which doubtless took the wind out of the sails of part of the base supporting Atalante and the alt-right groupuscules;

- the antiracist and antifascist movement also continued its sustained mobilization against the national-populist current, particularly what was its key vehicle throughout 2019, the Vague bleue.

The decline in activity on Québec’s far right doesn’t signal a victory for antifascist forces. To the contrary, with a majority populist government in the Assemblée Nationale, a government that moved rapidly in its first year in power to pass the racist Bill 21 (“an Act Respecting Laicity”) on state secularism, as well as gagging debate to adopt a variety of anti-immigrant measures, it is reasonable to postulate that the right-wing forces are simply taking a breather, because they feel they’ve achieved some of their main goals. That said, the relative calm has been an opportunity for us to do the work necessary to deepen and refine our analysis, which has led us to define two broad tendencies on the far right. (For more, see Between National Populism and Neofascism: The State of the Far Right in Québec in 2019.)

Now we’re going to take the opportunity present an overview of the most important groups active on the Québec far right in 2019 and of their key actions up to the COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020, which we can presume will be a key turning point (and not just for them).

///

The Nationalist-Populists

The Gilets jaunes du Québec (GJQ) and Pierre Dion

Part of the core of the so-called “Gilets jaunes du Québec”, in Montréal for the Pride parade, on August 18, 2019, where they hoped to heckle Justin Trudeau.

The GJQ is made up of a handful of identitarian militants with no ties to any organized group who share as a common denominator a “post-factual” and conspiratorial approach (the sort that suggests that G5 technology is part of a New World Order plot, to provide just one example) and an intellectual vapidity (Fred Pitt, Iwane “Akim” Blanchet, Michel “Piratriote” Ethier, and their ilk). They come together in different tiny groups networked together in different areas of Québec—at most there are two dozen of them in Montréal. The GJQ took shape on Facebook in December 2018 on the basis of a shared interest in the French Gilets jaunes. Their understanding of that movement is, however, entirely incorrect. They mistakenly think that it is a revolt against the “globalist” elite. They met online in December 2018, and, in 2019, they began assembling under the rubric of the GJQ in front of the TVA building in Montréal on the first Saturday of every month to denounce the network’s biased journalism. (Far be it from us to defend TVA or any other organ of the Québecor group, which we consider one of the primary vectors for the retreat into identitarianism and xenophobia that we have witnessed since the so-called reasonable accommodations crisis of 2007 and the resultant rise of national-populism in recent years. Whether the result of the obfuscation introduced by various conspiracy theories or of a basic intellectual mediocrity, the so-called Gilets jaunes du Québec don’t seem to understand that TVA and the Journal de Montréal are objectively their allies in consolidating an identitarian movement in Québec. It’s worth noting that the first Vague bleue also took place in front of TVA in Montréal, on May 4, 2019.)

Some of the more strident Gilets jaunes (Michel Meunier and Luc Desjardins) subsequently joined the groupuscule known as the Gardiens du Québec (LGDQ, see below) and were among the most committed Vague bleue militants.

The uncategorizable crank Pierre Dion, who first appeared on our radar in 2018 when he tried to organize a and anti-immigrant demonstration in Laval, and who, in 2019, became widely known as a “troll” thanks to a Télé-Québec report, has been a sort of Gilets jaunes figurehead. (For more, see Report Back on the March 16 Solidarity Vigil/Counter-Demo in Montréal, March 16, 2019.)

On August 18, hoping to be able to heckle Justin Trudeau, Pierre Dion and a handful of Gilets jaunes du Québec knuckleheads went to Montréal’s Pride parade and harassed the participants.

The Gardiens du Québec (LGDQ)

(Left to right, wearing white t-shirts): Jean-Marc Lacombe, Stéfane Gauthier, Carl Dumont and Luc Desjardins, of the so-called “Gardiens du Québec”. Centre (with the blue hoodie), Jonathan Héroux, aka John Hex.

LGDQ is a small group of fifteen or so militants organized in the Bécancour/Trois-Rivières region. The group is centered around the couple Martine Tourigny and Stéfane Gauthier, and most members seem to be part of their extended family. Most likely, the members come from La Horde, an ephemeral La Meute splinter group. LGDQ has a team of medics and a security team judiciously dubbed the SOT (Sécurité opérationnelle sur le terrain [operational security in the field]; in reality this is the same gaggle of wannabe vigilante weirdos assembled by Stéfane Gauthier to “protect” national-populist gatherings.)

By rallying some Montréal militants (primarily members of the Gilets jaunes du Québec) and collaborating with John Hex (Jonathan Héroux, a militant with close ties to Storm Alliance), LGDQ became the main organizing force behind the Vague bleue in Montréal (in May) and in Trois-Rivières (in July).

Over the course of the year, LGDQ began to crumble under the toxic and racist influence of Michel “Mickey Mike” Meunier, who, most notably, recruited Joey McPhee (alias Joe Arcand, a neo-Nazi poser) into the group. Along with Luc Desjardins, he was probably behind the sad little gathering at the foot of the cross on Mont Royal in November 2019. From what we could see, this “demonstration” only included four individuals, all members of LGDQ, i.e., Michel Meunier, Luc Desjardins, Nathalie Vézina, and Joey McPhee. The group was apparently “all worked up” by a (false) rumour that McGill University was going to purchase and dismantle the cross on the mountain. No doubt in the hope of making the best of the situation, the “guardians” of Québec took the time to take selfies while doing Hitler salutes before descending.

(From left to right) Michel Meunier, Luc Desjardins, Nathalie Vézina and Joey McPhee, of the “Gardiens du Québec”, do the nazi salute on the Mont Royal, November 3, 2019.

On November 22, a few days after their “masterstroke” on the Mont Royal, LGDQ got all worked up again. That day, a demonstration was called at Victoria Square against “l’ensemble des politiques identitaires portées par Simon Jolin-Barrette et la CAQ” [all the identitarian policies of Simon Jolin-Barette and the CAQ], particularly targeting reforms to the PEQ (the Programme de l’expérience québécoise, which allows foreign students to more rapidly be accepted in Québec, making them admissible as permanent residents in Canada). This demonstration was organized by UQAM student associations and the Syndicat des étudiants et étudiantes employé-e-s. About 150 people participated. Eight militants from the LGDQ and the Gilets jaunes du Québec orbit gathered a few metres from the demonstration, shouting “You must submit” and “Québec is secular” at the student protesters. As they approached the demonstration, LGDQ was confronted by some antifascists who were present. After a little bit of commotion, the police intervened to separate the two groups. The demonstration then proceeded without further incident but with a heavy police presence.

All year, a conflict was slowly brewing between LGDQ and the Groupe Sécurité Patriote (GSP—we’ll get to them below), until finally the two groups traded blows during the demonstration in Saint-Bernard-de-Lacolle on October 26.

It is worth dwelling for a moment on the case of Michel “Mickey Mike” Meunier. In 2019, he established himself as one of the most active far-right militants in Montréal, and certainly one of the nuttiest of this collection of fruitcakes. Throughout the year, but particularly during the period leading up to the Vague bleue, Meunier was in the habit of wandering the streets of the Centre-Sud and Hochelaga neighbourhoods of Montréal tearing down or covering up any sign of a left presence, replacing it with stickers, posters, or graffiti of a racist and identitarian nature. He also posted numerous fairly surreal videos exhibiting an unhealthy obsession with antifascists—for example, one which showed him pissing on an antifascist sticker in the toilets of the Comité social Centre-Sud. In December, Meunier was arrested (but seemingly never charged) for threats he made online against Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Since Meunier’s arrest, the “guardians” have been extremely discreet, which can be seen most clearly online. Meunier resurfaced recently on Facebook in a major beef with Storm Alliance, which he accuses of having betrayed him. . . He has also returned to his habitual identitarian stickering in Montréal’s Centre-Sud neighbourhood.

A sample of the stickers posted by Michel “Mickey Mike” Meunier all over the Centre-Sud and Hochelaga neighbourhoods of Montréal.

The “Vague bleue”

(From left to right) Guillaume Bélanger, Stéfane Gauthier, Michel Meunier, Jonathan Héroux and Luc Desjardins were some of the most enthusiastic promoters of the “Vague bleue”.

The so-called Vague bleue (Blue Wave) was primarily a mobilization of the national-populist groups that existed in 2019, at least of those outside of La Meute’s orbit as the latter group increasingly lost its pull. At its origin, the Vague bleue movement hoped to be some sort of popular vehicle for achieving a Québec “citizen’s constitution,” but it quickly took an Islamophobic turn and reoriented its message primarily around a fanatical support for Bill 21 and “a secular state.”

If the first iteration was a relative success (three to four hundred people in Montréal on May 4), in spite of an aggressive antiracist countermobilization, the second demonstration (in Trois-Rivières, on July 27) was a crushing defeat, not drawing more than eighty people. This is when Diane Blain gave her infamous speech oozing with racism, which received a certain amount of media coverage and probably undermined any potential future comeback for Vague bleue. (Diane Blain had already scored headlines when, as a La Meute member, she heckled Justin Trudeau on August 16, 2018, during a PR exercise in Sabrevois, not far from Lacolle. Like many others, she has since quit La Meute, but nonetheless remains very active in the far-right national-populist scene in Québec.)

The second edition of the “Vague Bleue”, in Trois-Rivières, on July 27, 2019, was a complete debacle.

Montréal Antifasciste produced a number of articles and communiqués about Vague bleue and its militants:

- “Vague bleue”: the racist, Islamophobic Fringe of Québec Nationalism Comes Out to Play (April 26, 2019)

- “Blue Wave” Hits a Wall in Montréal: Antifascists Force a Nationalist Identitarian Demonstration to Hide (Yet Again) Behind the Police (May 6, 2019)

- “Vague bleue,” the Last Stand of Québec’s Far-Right Soldier Wannabes (June 28, 2019)

- Vague bleue 2: Xenophobes Suffer an Epic Defeat in Trois-Rivières (July 28, 2019)

Storm Alliance (SA)

The absence of leadership in Storm Alliance was confirmed in 2019, proving that the group grew too quickly and never really found its feet after the departure of it founder Dave Tregget. With the implosion of La Meute, many defectors would follow the lead of Steeve “L’Artiss” Charland and gravitate toward SA.

SA is increasingly irrelevant and apart from its contribution to the Vague bleue bully squad didn’t do anything of note in 2019. Nonetheless, we can note the “for the children” demonstration in Québec City in September, under the impetus of the conspiracy theorist and serial litigant Mario Roy, who has been on a crusade against the Directeur de la Protection de la Jeunesse (DPJ) for years now. (Roy, a prominent SA member, made headlines earlier in 2019, when he received a quarter of the donations to a fund to support the family of a young girl killed in Granby to finance his personal crusade!) SA attempted a relaunch during the holiday season with a “food baskets for families in need” campaign, its umpteenth attempt to reinvent itself and clean up its image by showing a social conscience. At least the “stormers” aren’t foaming at the mouth about refugees down at the border when they are busy filling food baskets at IGA or demonstrating “for the children.” Meanwhile, their Facebook group, their main mobilizing tool, seems to be at death’s door.

La Meute

Not much to say about La Meute, by far the most important and best structured national-populist group, with the largest membership . . . until its breathtaking collapse in 2019. The previous year, 2018, had gone well for La Meute, with lots of media coverage when they released their manifesto and a number of high-visibility actions during the provincial election campaign. The group even took credit for the CAQ victory and the defeat of the Liberals under Philippe Couillard, and signaled their intent to be very present in 2019. The duo of Sylvain “Maikan” Brouillette, their ideological spokesman, and Steve “L’Artiss” Charland, keeping things together within the group, seemed to be working well, but in the end internal dissension proved to be stronger than group solidarity. In a dramatic gesture not lacking in panache, Charland left the group, burning his La Meute colours on June 24, 2019, in the company of a number of clan chiefs and members of the council. (It would be tedious of us to present a detailed description of the conflict, but anyone interested can consult the related endnote.)[i] At this point, Charland’s clan members seem to have either thrown in the towel or defected to Storm Alliance, leaving Sylvain Brouillette as uncontested leader of an online organization which he keeps under his thumb with the help of “la Garde,” his red-pawed supporters.

In short, La Meute was largely insignificant in 2019, and nothing suggests the likely return of the organization in 2020.

Groupe Sécurité Patriote (GSP)

The GSP began as an (in)security group for the Front patriotique du Québec (FPQ), before gradually becoming independent, although the groups remain close and still collaborate from time to time. The GSP also patched over some members of the Montréal III%. It’s a small, highly structured group of some fifteen people under the leadership of Robert “Bob le Warrior” Proulx, who is known for his annoying propensity for waving the Mohawk Warrior flag at identitarian demonstrations, as well as for his affinity with the boneheads in the Soldiers of Odin.

GSP’s boss, Robert Proulx, cozying up to notorious neonazi Kevin Goudreau, in St-Bernard-de-Lacolle, August 24, 2019 .

Overall, the year brought a series of pronounced defeats for the GSP, including a pathetic pro–Bill 21 demonstration in Montréal on June 8 (twenty people turned out, basically consisting of the GSP’s active members), the FPQ’s annual July 1 demonstration, and their exclusion from the Vague bleue in Montréal on May 4, for what was seen as their overly paramilitary posture. In the late summer of 2019, the GSP had the notion of regularly demonstrating at the border in Saint-Bernard-de-Lacolle to protest irregular immigration and demand the closure of Roxham Road. In the end, the group organized two demonstrations. The first (August 24) was initially proposed by Lucie Poulin from the Parti Patriote and had fifty participants, including a number from Ontario, among them that sad little neo-Nazi Kevin Goudreau. The second (October 19) drew around 120 people, remobilizing a section of Québec’s far right, which had been very divided since the Vague bleue defeat and the collapse of La Meute.

This second demonstration could be seen as a success, leaving antiracist activists worried that this mobilization might gain some traction . . . but, in the end, it carried within it the disease of discord. In effect, the far-reaching tensions between the GSP and LGDQ, which had been to some degree kept under wraps until that point, burst out into the open at the demonstration and in its aftermath.

- III% Québec Member Caught Proposing Fake Terrorist Attack (April 8, 2019)

- Dozens of So-Called Québec “Patriots” Join Forces with Canadian Neo-Nazis and Ultra-Nationalists to Demonstrate against Immigrants in Lacolle (August 27, 2019)

The People’s Party of Canada and the Federal Elections

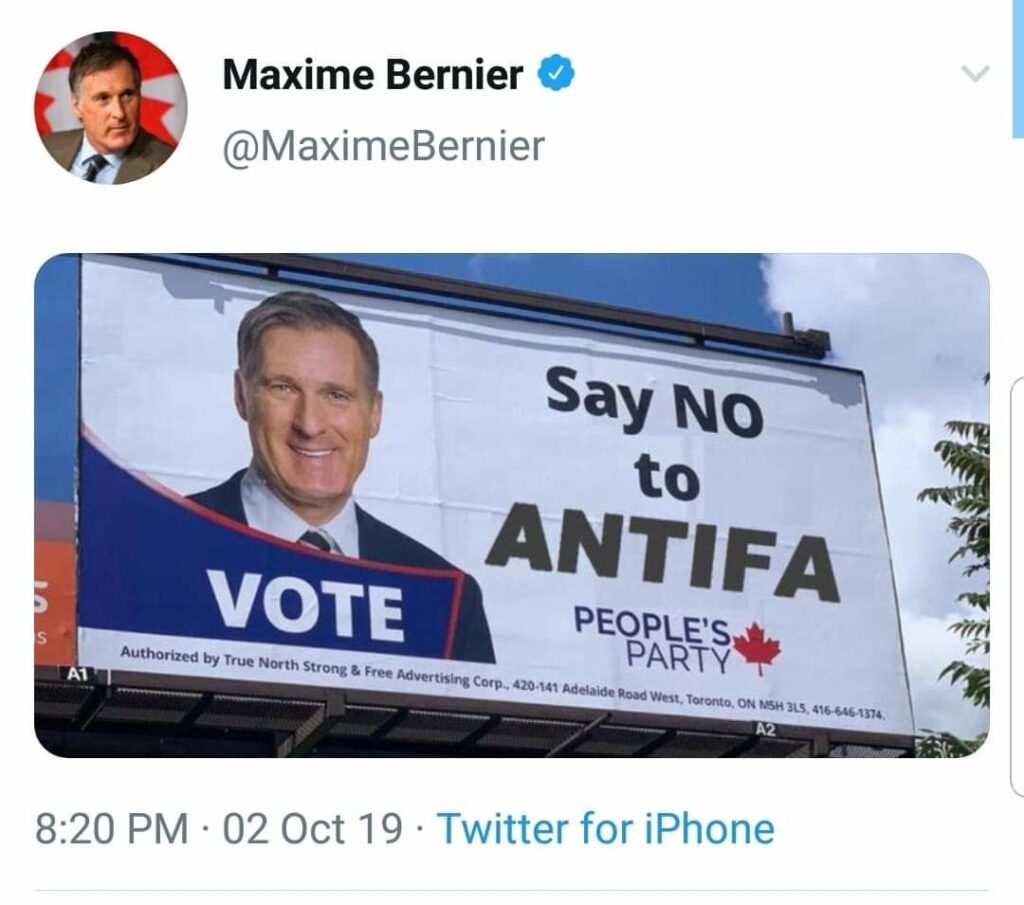

On October 21, 2019, Justin Trudeau was re-elected Prime Minister du Canada, at the head of a minority Liberal government. These were the elections that brought Maxime Bernier and his political pretensions into direct contact with reality. Bernier had long been the Conservative MP for Beauce, before leaving the fold to create the People’s Party of Canada (PPC) in 2018, hoping to outflank the Conservatives on the right.

From the outset, the PPC adopted anti-immigrant and climate change denial positions, and when its rallies were treated as legitimate targets by the radical left, Bernier was not shy to call out “antifa” as terrorists. The PPC gained the support of national-populists across Canada, although this support was somewhat undermined in Québec by a certain opposition to Canadian nationalism. (The minuscule and incompetent Parti Patriote, led by Donald Proulx, unsuccessfully attempted to consolidate this nationalist opposition.) Bernier was also frequently criticized for welcoming different elements of the far right with open arms, even posing for photos with members of the Northern Front and the Soldiers of Odin.

Despite its leader’s ambitions, the PPC failed miserably, not having a single candidate elected and winning only 2 percent of the popular vote (even its fearless leader Maxime Bernier only scored 3 percent in a riding he had held as a Conservative MP for thirteen years). This defeat was undoubtedly in part the result of a widespread sense on the right that the PPC had no chance of unseating the Liberals, which was their main priority. As a result, many ambivalent national-populists in Québec voted for the Conservative Party or the Bloc Québécois. (It should be noted that while the leadership of the Bloc said that it would not tolerate far-right militants in its ranks, the media uncovered a number of candidates who frequently posted racist and far-right messages on social media.)

- Maxime Bernier’s PCC and the Far Right (October 17, 2019)

The Neofascists

Fédération des Québécois de Souche

This sticker depecting Québécois pianist André Mathieu, presumably produced in the entourage of the Fédération des Québécois de souche, was posted by Atalante militants in Quebec City and Montréal over the summer 2019.

The FQS does not have an active public presence (it leaves that to its sister organization Atalante). It plays a role in providing a space for neofascists to network and spreading far-right ideology on its very active Facebook page and through its magazine Le Harfang. Over the course of the year, it produced stickers that were primarily seen in the Québec City area, carried out some postering actions, and organized a gathering in Québec City in support of the nascent Gilets jaunes movement. In April, the FQS’s “brief” on Bill 9 on immigration was deposited with the commission by the CAQ deputy for Châteauguay Marie Chantal Chassé. The brief was removed from the Assemblée Nationale’s website the next day, when Québec Solidaire pointed out the racist nature of the FQS.

Atalante

A couple dozen fans attend a concert by Atalante’s flagship band Légitime Violence and French NSBM outfit Baise Ma Hache, at Bar le Duck in Québec City, on June 8, 2019; earlier that day anti-fascists pressured the management of a local community center to cancel a reservation made for this concert under false pretences.

Atalante continued its normal activities (nature hikes, postering, distributing sandwiches on the street, and workshops), primarily in Québec City and Montréal, where its attempts to sink roots do not, however, seem to be working. We have been able to observe stagnation in its membership, and some paltry recruiting efforts in Saguenay, where the organization doesn’t have more than a handful of sympathizers. The two main incidents of note involving Atalante in the last year were its role in a concert by the French National Socialist Black Metal band Baise Ma Hache in June 2019 (partially disrupted by the antifascist milieu) and the trial of its leader Raphaël Lévesque.[2]

Antifascists dogged them incessantly:

- Unmasking Atalante (December 19, 2018)

- Atalante and Its Sympathizers—Part 1: Heïdy Prévost, the Influencer (February 12, 2019)

- Atalante and Its Sympathizers—Part 2: Folk You! and the Far-Right Infiltration of Folk Music (May 15, 2019)

- Atalante and Its Sympathizers—Part 3: Louis Fernandez and Baptiste Gilistro . . . the French Factor (July 25, 2019)

- Chasing Atalante: Where Do the Fascists Work? (September 29, 2019)

- Debunking Atalante: Not Nazis but. . . Yeah Actually (December 5, 2019)

- Raf Stomper’s Trial in Montréal: A Losing Proposition. . . Except for the Man at the Center of It (December 12, 2019)

The Alt-Right

Julien Côté Lussier called his nazi pal Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald for backup, in Verdun, October 19, 2019.

The organizational core of the Montréal alt-right blew apart in 2018, and most of its key figures fled Québec or disappeared into the shadows. The news of the year was Julien Côté running in the federal elections and his call for backup from his neo-Nazi comrade Shawn Beauvais-MacDonald, also an Atalante militant. In the meantime, we found out that Beauvais-MacDonald had left his Securitas job to spend some time at the Centre intégré de mécanique, de métallurgie et d’électricité, which, we learned, earned him a visit from antifascist militants. Other than that, the alt-right has followed the same arc in Montréal as elsewhere in North America and has practically no IRL existence, besides harassing the owners of a café in Val David, which, in all likelihood, was the work of members of the alt-right living in the area.

Additionally, the leak of the discussion logs from the Iron March forum in November made it possible to identify some Québécois alt-right activists, some of whom were also active in the Alt-Right Montréal chatroom on Discord.

- Athan Zafirov, the Montréal Neo-Nazi Scumbag Who Thought He Could Get Away with It. . . (February 17, 2019)

- Julien Côté Lussier: The Hubris of a Neo-Nazi Who Hoped to Get Elected (November 4, 2019)

- Alexander Liberio: Metalhead, Nazi. . . Christian Orthodox Seminarian (November 21, 2019)

2020 so far. . .

In 2020 the political spotlight was captured by a wave of Indigenous resistance across Canada. This unanticipated but in many ways inevitable historic development clearly took the far right by surprise.[3]

In English Canada, national-populists and neofascists were united in their ferocious opposition to the demands of Indigenous people defending their sovereignty. In Edmonton, on February 19, elements of the far right associated with the group United We Roll dismantled a solidarity blockade, calling for others to do the same across the country. There were also numerous bomb threats against Indigenous militants, and Indigenous communities across Canada were targeted by an endless stream of racist commentary, both at the blockades and on the street. The English Canadian far right was pretty much unanimous in its hostility to solidarity blockades, drawing on both its trademark racism and a strong current of climate change denial anchored in conspiracy theories about “globalist” elites secretly financing these disturbances, international conflicts, ecological movements, etc.

In Québec, the initial reaction was quite different. Even if many Québec national-populists are racists, climate change deniers, and aficionados of the ridiculous conspiracy theories developed by their cousins in other provinces, their reaction to the blockades was generally one of confusion. In the early days of this wave of resistance, one of the primary issues raised in their networks was the alleged “double standard,” as they felt that if they did blockades they would be arrested and repressed, whereas they saw the solidarity blockades as being tolerated. At the same time, there were isolated examples of far-right activists expressing their solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en struggle. The distinctions between the reactions inside of and outside of Québec is doubtless the result the different postures adopted by national-populists in Québec and those in English Canada toward the Canadian nation-state.

Nonetheless, after the first week of solidarity actions, particularly the key blockade in Kahnawake and the solidarity blockade in Saint-Lambert, the national-populists rediscovered their historic antipathy for the Mohawk nation. This reversal put an abrupt end to the hypocritical pantomime we’ve been forced to live with for several years now, whereby the far-right leadership and many rank-and-file far-right militants pretended to be the natural allies of Indigenous people in their struggle with the Canadian state. Suddenly, this was no longer the case, and the anti-Indigenous comments and threats began to multiply in Québec far-right social media networks. None of which translated into any tangible action, however, in part because some of the key players still couldn’t figure out how to position themselves. Beyond that, the far right was organizationally too poorly prepared to effectively intervene.

In mid-March 2020, as COVID-19 quickly went from being news from far away to a global pandemic necessitating a near-global lockdown, the Quebec far right was similarly incapable of acting. While left-wing forces organized mutual aid groups and even carried out “car demonstrations” in solidarity with migrants facing murderous conditions in detention centers, far rightists were confined to social media, their chief occupation being to debate and propagate various conspiracy theories about the virus, for instance the idea that it is spread by 5g wireless technology.

A future defined by uncertainty. . .

The specific wave of far right activity that began in 2016 seems to have finally collapsed in 2019, and what we have been dealing with since then have been a series of largely unsuccessful or unsustainable attempts to regroup and move forward. This weakness of our opponents can be seen in their inability to respond to either of the two main issues in 2020 so far. That said, their base shows no sign of dissipating, and conspiratorial and racist thinking offer a wide base of potential support far beyond their current ranks.

As we stated above, their current disarray cannot be viewed simply as a victory on our part. Today, two of the main demands of the far right for the past several years have been satisfied – Law 21 prohibits people wearing “religious clothing” from working in various public sector jobs (this primarily targets Muslim women who might wear hijab), and in the context of the pandemic Roxham Road has been closed off to asylum seekers. The radical left, inside but also beyond the antifascist milieu, has its work cut out for it.

The new situation created by the pandemic is replete with danger and uncertainty. In the coming months, new political opportunities will be accompanied by a strong wave of politics based in fear and scapegoating. In that light, we encourage you to read our Covid-19: Preliminary Thoughts on the Current Situation (March 30, 2020).

Both vigilance and solidarity remain essential.

[1] For posterity, and for those of you with a morbid fascination for this sort of train wreck, here’s the broad strokes of what went down.

A conflict within La Meute burst into the open in May 2019, when it became clear the group’s spokesman (and de facto leader) Sylvain Brouillette was unable to provide the necessary paperwork for the La Meute Inc. financial year 2017–2018. Members of the executive where disturbed by how it would look if they were unable to answer clan members’ questions (regional La Meute sections are called clans) and by the fact that this, once again, prevented La Meute from applying for nonprofit status. Meanwhile, Brouillette defended himself by hiding behind personal problems (a contentious divorce and professional difficulties) and whining about never having wanted to be responsible for accounting. For their part, other members of the executive accused him of monopolizing power, controlling information, and running La Meute like it was his private fiefdom.

As the tensions increased, all of the members of the executive (except Brouillette) quit. Brouillette stripped Stéphane Roch of his role as La Meute’s public Facebook administrator, and, as a reprisal, Brouillette was stripped of his administrative responsibility for the organization’s secret Facebook page. On June 19, 2019, it seemed as if Brouillette had been ousted from the organization, with his critics (grouped around Steeve “L’Artiss” Charland) seizing the reins, but, a few days later, Brouillette managed to regain control of the secret Facebook page, and Charland and his cohort found themselves looking at the door.

One of Brouillette’s first actions, once he regained control, was to publish the figures from 2017–2018 financial year. Even if this report wasn’t detailed enough to satisfy the demands of Revenue Canada, it revealed an organization functioning on a shoestring budget, with receipts in the neighbourhood $10,000. Half this budget was logged as “donations from the Chinese,” probably a reference to the Chinese Canadian Alliance, an “astroturf” group that organized the demonstration at Parliament Hill in Ottawa, on February 18, 2018, which La Meute, Storm Alliance, and other groups joined. (At the time, Brouillette said: “La Meute has built a solid alliance that we believe opens the door to alliances with other communities in the near future” . . . presuming they’re ready to pay for the honour, we conjecture!)

To dramatize the conflict, many former members made it a point of honour to celebrate Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day by burning and destroying their La Meute clothes and baubles (ballcaps, leather vests, flags, etc.), declaring La Meute “dead.” Nonetheless, the clans seem to have accepted Brouillette’s return.

Whatever the case may be, at the time of writing (April 2020), the group has been inactive since the events described above.

[2] Raphaël Lévesque is accused of break and enter, mischief, and criminal harassment of the journalist Simon Coutu and other VICE employees. The thirty-six-year-old man is also accused of intimidating Simon Coutu to pressure him to abstain from “covering the activities of the group Atalante Québec”. Coutu had published several articles about the far right in the previous weeks. See https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/justice-et-faits-divers/201912/09/01-5253022-intimidation-a-vice-le-leader-dun-groupe-dextreme-droite-en-cour.php.

[3] As Solidarity Across Borders explained: “In December, a British Columbia Supreme Court judge granted an injunction against the land defenders at the Unist’ot’en Camp, who have for years maintained a blockade to prevent construction of the Coastal GasLink (TransCanada) pipeline project, which would run through unceded Wet’suwet’en territory. A second blockade camp has been established by another Wet’suwet’en clan, the Gidimt’en, showing united opposition to the pipeline within their traditional governance structures and in defiance of a legal ruling that refuses to acknowledge their sovereignty and title. In the last few days the RCMP has imposed a media blackout as they stage a large-scale invasion of Wet’suwet’en territory to dismantle the blockades. Land defenders have made an urgent call for solidarity and support, in the face of what they have called “an act of war,” and “a violation of human rights, a siege, and an extension of the genocide that Wet’suwet’en have survived since contact.””